Beijing (AFP) – China’s meteoric rise as the world’s powerhouse of electric vehicle production makes Western efforts to curb their exports a tough sell — and means they could even stifle the fight against climate change, analysts warn. EU states are expected to vote Friday on whether to impose hefty tariffs on imported EVs from China — part of a bid to protect its automotive industry from low-cost, subsidised competition. And the United States has sought to stop a flood of cheap Chinese electric cars from flooding its markets, undercutting its own car giants and pricing out American workers.

Western powers have long raised concerns about the risks of Chinese “overcapacity,” fuelled by Beijing’s vast industrial subsidies and waning consumption at home. But experts say that with the West keen to hit ambitious climate goals and the need to speed up the transition to green energy, it can ill-afford to prop up its stagnating car industry. “There is no way the EU and US can reach their climate goals within the timeframes they’ve originally articulated without the help of Chinese EVs,” Tu Le, managing director at Sino Auto Insights, told AFP. “They’ll either need to reconcile their goals or allow some entry of Chinese EVs.”

China long lagged the West in its auto sector and in the push for green energy to curb rising emissions, of which it remains the world’s largest producer. But a push to expand green energy production and reduce China’s emissions has seen production of EVs and their necessary components soar. That policy has led Beijing to more than $230 billion for the EV industry between 2009 and 2023, analysis by Washington’s Center for Strategic and International Studies found.

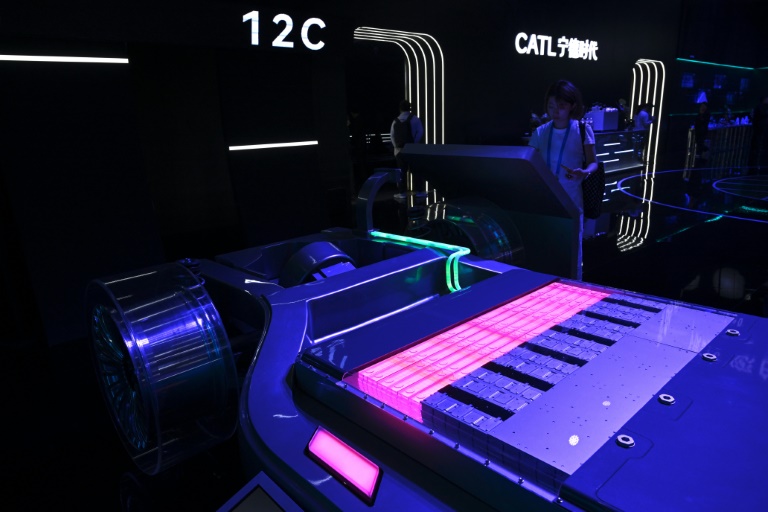

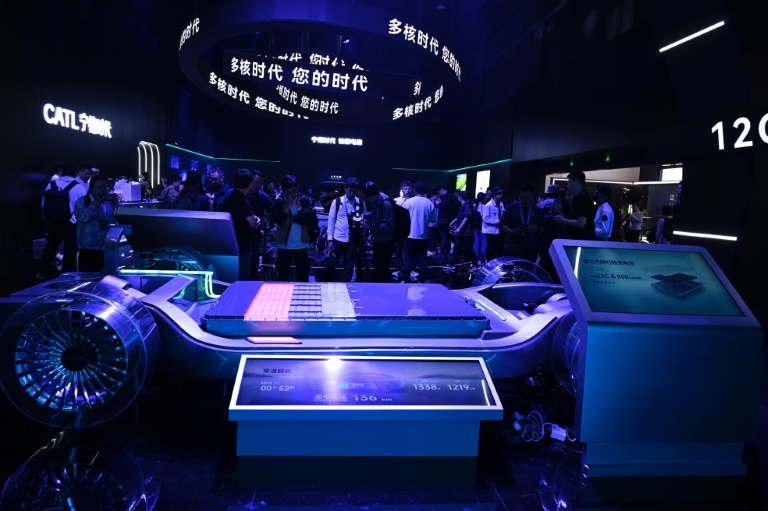

Subsidies and support from Beijing have been “key players in the rapid growth of China’s EV market,” MingYii Lai, a consultant at Daxue Consulting, told AFP. That push has seen Chinese car giants like BYD — once known for making batteries — post record annual profits for last year. In 2023, more than half of all electric vehicles sold worldwide were made by Chinese firms, according to the International Energy Agency. Much of that was driven by domestic consumption — of all new EVs sold globally in December, 69 percent were in China, according to the research firm Rystad Energy.

But China’s EV giants have made no secret of their overseas ambitions. BYD has said it hopes to be among the top five car companies in Europe and has plans to open factories in Hungary and Turkey. Chinese automakers are even making inroads in Latin America — they sold $8.5 billion of cars in the region last year, up from $2.2 billion in 2009, according to the International Trade Center, a UN agency. And analysts from consulting firm AlixPartners estimate Chinese companies will hold 33 percent of the global car market by 2030.

Washington has sought to boost its own domestic EV market, in July unveiling $1.7 billion in grants to help expand or revive auto facilities for making electric vehicles and parts. And the 2022 Inflation Reduction Act funnelled some $370 billion into subsidies for America’s energy transition, including tax breaks for US-made EVs and batteries. The rapid growth of their Chinese competitors has set off alarm bells in Washington and Brussels. “The fear is that these companies are gaining such a market share so quickly,” Ilaria Mazzocco, a senior fellow at the CSIS think tank, told AFP. “There is a push to electrify — and they have the best, cheapest EVs out there,” she said.

Analysts say the European Union simply can’t afford to take as hard a line as the United States, which has accused Beijing of “cheating” and imposed a 100 percent duty on electric vehicles from China. “German automakers rely so heavily on the China market for its profits,” Sino Auto Insights’ Tu said. “The two largest European automakers now have significant stakes in Chinese EV brands…it’s in their best interests that those companies are successful,” he added, referring to Stellantis and Volkswagen. Those firms “have already waved the white flag and decided they can’t compete and would rather partner.”

That is also complicated by the global push to reduce emissions. “The urgency of combating climate change needs the world to move faster to advance the energy transition in all sectors, and calls for more clean power and more EVs on the road,” analysts at the US-based sustainability think tank RMI wrote in August. “China can provide the world with cleaner, high-quality and affordable vehicles,” they said.

The European Commission under Ursula von der Leyen drove through an ambitious legislative “Green Deal” including flagship measures such as a ban on new combustion engine cars from 2035. But without a steady stream of electric vehicles on Europe’s roads, analysts say, that goal will be tough to meet. While the EU’s efforts “aim to protect local industries and ensure fair competition, they could inadvertently limit the availability and affordability of EVs,” Daxue Consulting’s Lai said. “This might…slow down the transition to electric vehicles, which is essential for tackling climate change.”

© 2024 AFP