Colombo (AFP) – Sri Lanka’s new leftist leader has little room to renegotiate an IMF bailout that threw a lifeline to his bankrupt country but imposed punishing and unpopular austerity measures, analysts say. Anura Kumara Dissanayake, 55, was a vocal critic of global lenders from the fringes of the island nation’s politics, including in the aftermath of Sri Lanka’s unprecedented economic meltdown two years ago. He won Saturday’s presidential vote in a landslide promising to reverse steep tax hikes, raise public servant salaries and renegotiate the International Monetary Fund rescue package secured by his predecessor.

But after his inauguration two days later, he appealed for international support to revive Sri Lanka’s economy, admitting he had no magic solution to its woes. “There are certain red lines that the IMF will not agree to negotiate,” Murtaza Jafferjee of the Colombo-based economic think tank Advocata told AFP. He said the Washington-based lender of last resort would be very unlikely to budge on core components of its $2.9 billion bailout, including a ban on printing money and revenue and spending targets agreed by the last administration.

Dissanayake’s party, the People’s Liberation Front (JVP), sports the hammer and sickle motif of the international communist movement on its logo. The JVP was confined to the political wilderness for decades after leading rebellions in the 1970s and 1980s that left more than 80,000 people dead, before the party renounced violence. Months of food, fuel, and medicine shortages that accompanied the 2022 financial crisis and foreign debt default rallied the public behind it.

Dissanayake’s call to upend the island’s “corrupt” politics resonated with a public infuriated by chronic economic mismanagement and graft scandals in government ranks. As the size of his victory became clear, his party moved quickly to assure markets and creditors that it would adhere to the broad strokes of the bailout deal. “We will not tear up the IMF programme,” JVP politburo member Bimal Ratnayake said. “It is a binding document, but there is a provision to renegotiate.” The ironic outcome of the pledge was that the same day as an avowed Marxist assumed the presidency, Colombo’s stock exchange rallied by 1.5 percent.

But by committing to maintain the rescue plan, Jafferjee said that any tweaks pushed by Dissanayake would necessarily be minor. “On the fiscal side, there is not much adjustment that can be done,” he said.

Dissanayake’s predecessor, Ranil Wickremesinghe, was voted out of office after doubling income taxes and imposing other reviled austerity measures. His policies ended the shortages as well as runaway inflation and returned the country to growth but left millions struggling to make ends meet. The IMF said Wickremesinghe’s administration had made a great deal of progress in repairing the nation’s ruined finances after a $46 billion foreign debt default two years ago. But spokesperson Julie Kozack also warned ahead of the presidential poll that Sri Lanka was “not out of the woods yet.”

One of Dissanayake’s first acts of business will be to secure a parliamentary endorsement for a debt restructuring deal with international bondholders, negotiated by his predecessor at the eleventh hour and announced last week. That will have to wait for the election of a new parliament, as Dissanayake sought to capitalise on his landslide win by calling snap polls on Tuesday, the day after he was sworn in. Umesh Moramudali, an economics lecturer at the University of Colombo, warned that failing to secure the deal’s passage could open Sri Lanka to legal action from its creditors. “It would be in the best interest of the country to avoid litigation with bondholders,” he told AFP.

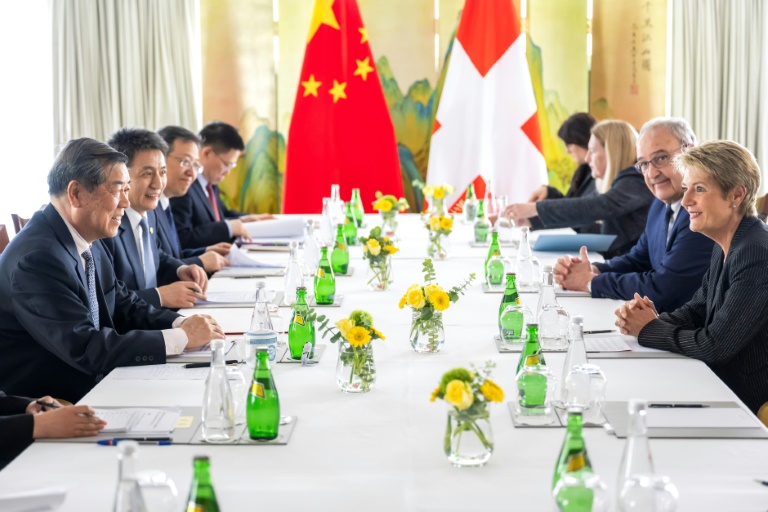

Sri Lanka also owes billions to China and India, its two largest bilateral creditors who are both competing for influence in the island nation, which is strategically situated on global east-west sea routes. Both nations have congratulated Dissanayake on his win and pledged to work with his administration. Dissanayake’s ideological leanings, his campaign against an India-backed energy project, and the JVP’s historical anti-India stance had led some experts to suspect his administration would lead Sri Lanka to a closer relationship with Beijing. But he used his inauguration speech to reject “power divisions in the world” and pledged to work with all other countries for the benefit of his own.

“The new leader’s foreign policy stance will be important,” said Farwa Aamer of the Asia Society Policy Institute. “It will be in his interest to work with India, as a regional partner, as he focuses on economic development.”

© 2024 AFP