Belfast (AFP) – Northern Ireland on Tuesday moved a step closer to ending a nearly two-year political deadlock after the main pro-UK party endorsed a deal with London aimed at reopening the region’s assembly.

The Democratic Unionist Party (DUP) walked out of the power-sharing government at Stormont in February 2022 to protest post-Brexit trade arrangements for Northern Ireland, which has the UK’s only land border with the European Union.

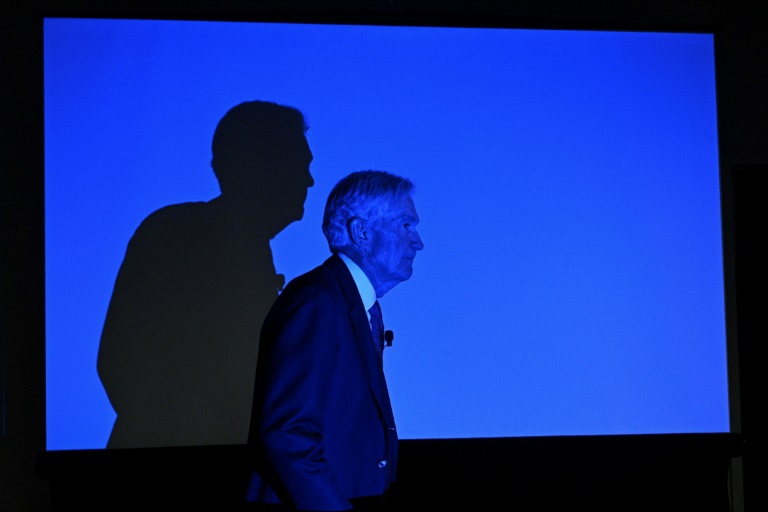

DUP leader Jeffrey Donaldson said the agreement, approved in an internal vote at a closed-door meeting, formed a basis to restore the Northern Ireland Assembly after nearly two years’ absence.

“The result was clear.The DUP has been decisive.I have been mandated to move forward,” Donaldson told reporters in the early hours, after a five-hour meeting and vote.

Details of the deal are expected as early as Wednesday, he told BBC radio, in a move that UK Prime Minister Rishi Sunak called a “positive step” towards restoring Northern Ireland’s institutions.

Sunak’s Northern Ireland Secretary Chris Heaton-Harris said the deal contained “significant changes…to make sure our internal market works properly”.

No renegotiations were expected with the European Union, and the deal would not likely face opposition in the UK parliament, he added.

The deal means the DUP and the nationalist pro-Irish Sinn Fein could elect a speaker for the assembly in the coming days.

It would also see Sinn Fein’s Michelle O’Neill become first minister — the first time a nationalist has held the post after her party overtook the DUP in the last Assembly election in May 2022.

On the nationalist Falls Road in Belfast, Ellen O’Connor, a 19-year-old student, said the return of the assembly was long overdue.

“It has been really immature on the DUP’s behalf, they had all these reasons why they wouldn’t go into government, but at the end of the day a lot of people around here feel that the real reason was because they didn’t want to play second fiddle to Sinn Fein,” she told AFP.

“But you can’t only play by the rules when it suits you, that’s not how democracy works.”

– Conundrum –

A key plank of the 1998 Good Friday Agreement, which ended three decades of sectarian violence over British rule in Northern Ireland, was to keep an open border with the Republic of Ireland, an EU member, to the south.

But Brexit threw up a conundrum — how to protect the European single market and customs union if the UK was no longer part of it, when there was effectively an open back door for goods to cross in and out via Northern Ireland.

The post-Brexit trading arrangements sought to square that circle, deciding that the EU-UK border for goods checks would run down the Irish Sea.

Unionists though are concerned the solution effectively puts Northern Ireland on the EU side of the border and the other three nations of the UK — England, Scotland and Wales — on the other.

They said that by keeping the province partly under EU law, that opened the door to Northern Ireland being reunited with the Irish Republic — a prospect they bitterly oppose.

Sinn Fein leader Mary Lou McDonald on Tuesday said with O’Neill installed and Stormont back, Irish unity was now within “touching distance”.

– Public services –

The DUP sought during talks to overhaul the trading rules, including reducing the number of checks on goods travelling between Northern Ireland and mainland Great Britain.

Its boycott of the assembly though paralysed Northern Ireland’s power-sharing institutions and fuelled political uncertainty and industrial unrest.

Public services crumbled as budgets were put in cold storage.

Earlier this month, 16 public-service worker unions coordinated a mass strike over pay, the biggest industrial action seen in Northern Ireland for decades.

London has offered the region a £3.3 billion ($4.2 billion) financial package to solve public service pay disputes on condition that the assembly reopened.

O’Neill told reporters on Tuesday that lawmakers now needed to come together to tackle years of what she called UK government under-funding.

“We have work to do,” she said.

Naomi Long, leader of the non-aligned Alliance party, said reform of public services needed “stable institutions” and would not stand another collapse.

But on the Shankill Road in Belfast, a unionist stronghold, Danny, a 76-year-old pensioner who gave only his first name, feared a repeat.

“That’s the thing here in Northern Ireland with the Protestants and Catholics: they just don’t agree, so it’s a bad government no matter what.They’ll never agree, it’ll happen again,” he told AFP.