Hong Kong (AFP) – Hong Kong is facing its toughest fiscal test in three decades following a painful run of mammoth deficits, with experts urging the government to make careful cuts as the economy wobbles. The Chinese finance hub last saw a string of deficits after the Asian financial crisis in the late 1990s, but their scale was a fraction of the HK$252 billion ($32.4 billion) shortfall in the 2020-21 fiscal year. Hong Kong has recorded annual deficits exceeding $20 billion in three of the past four years, according to official figures.

The city’s finance chief Paul Chan said Sunday that the deficits were caused by “multiple internal and external challenges” and that a new budget unveiled on Wednesday will tightly control public spending. While Chan earlier predicted a return to surplus in “three or so years,” a former government minister told AFP that the situation is “not just due to economic cycles” spurred by the coronavirus pandemic. “If you look at Hong Kong versus other economies in the region, for example Singapore, those other economies have done much better,” said Anthony Cheung, who oversaw transport and housing policies.

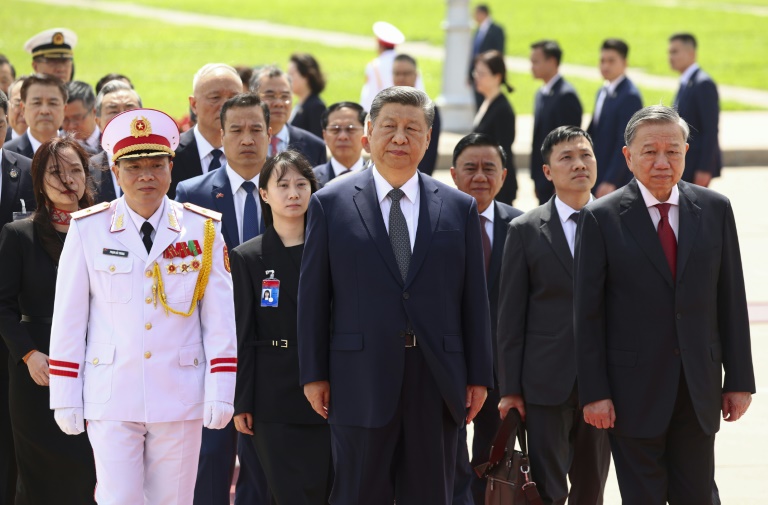

Adding to the headache is the exodus of companies and high-paid workers as the city’s international reputation took a hit after Beijing quelled pro-democracy protests and imposed a sweeping national security law in 2020. Singapore and Hong Kong suffered towering deficits in 2020 because of the pandemic, but the former has been able to keep spending relative to income in check as firms shift there from the Chinese city, helping it outperform its fiscal targets. The challenge for Hong Kong is not just to balance its books, but to find fiscal sustainability amid US-China tensions and a slowdown in the world’s second-largest economy, Cheung said. “In the past, we assumed that Hong Kong was geopolitically well-positioned… Now we have to be more careful about such presumptions.”

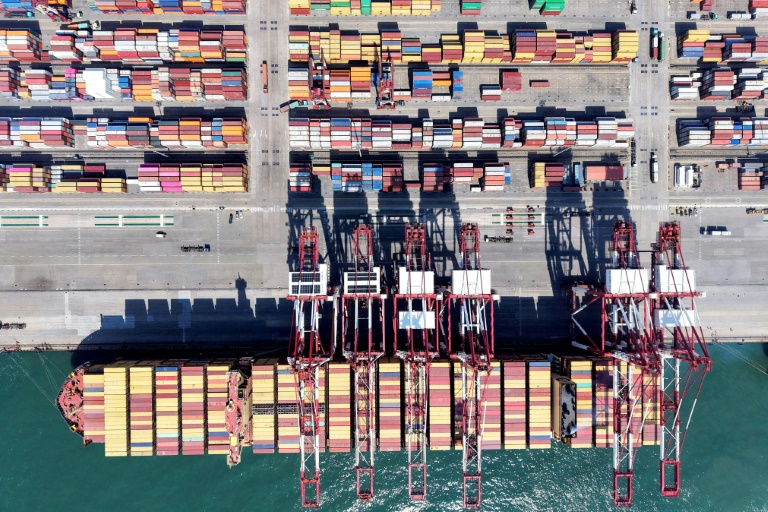

– Plunging land sales – Hong Kong is required by its mini-constitution to “strive to achieve a fiscal balance” — a holdover from British colonial rule that kept the market mostly free from government intervention. After returning to China in 1997, it kept taxes low and refilled its coffers with the help of land-related revenue, selling land to developers with deep pockets. But last year Hong Kong collected just $2.5 billion that way, from a peak of $21.2 billion in 2018. “(Land-related revenue) by itself has contributed to the majority of the income decline,” said Yang Liu, a financial economist at the University of Hong Kong. “We have a very inactive land market and declining housing prices. That’s one reason that people (don’t) trade, so there’s no tax (income),” Liu told AFP.

Hong Kong still has healthy cash reserves and low government debt compared with most economies around the world. But the prospect of three straight years in the red has fuelled public debate on how to spend less. “All the new initiatives will be under much stronger scrutiny, so (the government) will be a lot more disciplined, a lot more careful,” Liu said. In his upcoming budget speech, the finance chief is set to put the latest deficit at “under HK$100 billion,” adjusting for money raised from bond sales. There are calls to roll back a transport subsidy for those aged 60 to 64, which can grow into a major burden on the government as Hong Kong’s population ages. Lawmaker Edmund Wong cautioned against pay cuts for civil servants, which he said may cause private-sector employers to follow suit, but urged the government to slim down. “In the long term, we can greatly reduce the manpower which the government is employing now,” he told AFP.

– ‘Welcoming’ image – The deficits could prompt Hong Kong to rethink how it makes money, though past discussions on expanding the tax base — such as a goods and services tax — went nowhere. The city’s low ratio of debt to GDP — which the government last year put at no more than 13 percent — means it can afford to issue bonds to fund huge undertakings, experts say. Officials have signalled they will push ahead with a massive infrastructure project in northern Hong Kong while backing away from a separate plan to create artificial islands. As tensions flare between the United States and China, Hong Kong is seeking untapped growth potential in the Middle East and Southeast Asia that can translate to government revenue down the line.

The city’s economic fortunes are ultimately tied to how investors view the city as a regional and global hub, said Cheung, the former minister. “We have to continue to showcase Hong Kong as a city that welcomes all kinds of views, all kinds of people, so long as they stay within the parameters of the national security legislation,” Cheung said.

© 2024 AFP